|

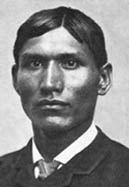

Ohiyesa (Charles Alexander Eastman) was born in a buffalo hide tipi near Redwood Falls, Minn., in the winter of 1858. His father, “Many Lightnings” (Tawakanhdeota), was a full-blood Sioux. His mother was the granddaughter of the Sioux Chief “Cloud Man” and the daughter of Stands Sacred (Wakan inajin win) and a well-known army officer, Seth Eastman. His name at birth was “Hakadah,” the pitiful last, because he became the last of his three brothers and one sister when his mother died shortly after his birth. In his early youth he received the name Ohiyesa (The Winner).

The baby was initially raised in his homeland of Minnesota by his grandmother. At the age of four, the so-called “Sioux Uprising of 1862” occurred and he became separated from his father, elder brothers and only sister, whom the tribe thought had been killed by the whites. Hakadah fled into exile in Manitoba with the remaining members of his band of Santee Sioux. For the next eleven years he lived the original nomadic life of his people in the care of his uncle and his grandmother. His uncle was a prominent hunter and warrior and gave the youth, now named Ohiyesa, the complete training necessary to carry on the nomadic tribal heritage, including all of the secrets of virgin nature. Both his uncle and grandmother instilled in him the spiritual philosophy of the Indian. Ohiyesa always regarded this period of his life as his most important education.

At fifteen, Ohiyesa had just entered Indian manhood and

was preparing to embark on his first war-path to avenge the reputed death of his

father, when he was astonished by the reappearance of his father. The young man

learned that this father had adopted the religion and customs of the hated race,

and was come to take home his youngest son.

His father was part of a small group of progressive Indians who earned a living

with a combination of farming and ranching on homesteads in Flandreau, Dakota Territory.

After Ohiyesa’s first experience with a mission day school, he contemplated rebelling

and leaving his new log home to return to the wild and his native ways. However

after a long discussion with his father, he cut his long hair, began to wear white

man’s clothing and applied himself to his new school life. He soon overcame his

reluctance, although not his unhappiness with his new world, and two years later

walked 150 miles to attend a better school at Santee, Nebraska. In this larger school

he made rapid progress and upon the recommendation of his teacher, the renowned

missionary educator, Dr. Alfred L. Riggs, Ohiyesa was accepted at to the preparatory

department of Beloit College, Wisconsin. His father had adopted the English name

of his wife’s father, Eastman, so the boy now named himself Charles Alexander Eastman.

Ohiyesa, now primarily known as Charles Eastman, spent two years at Beloit College

before successively going to Knox College, Ill.; then Kimball Union Academy in New

Hampshire, and finally to Dartmouth College. He graduated from Dartmouth in 1887,

and then studied medicine at Boston University, where he graduated in 1890 as orator

of his class. He spent a total of seventeen years in primary, preparatory, undergraduate

college, and professional education, which is significantly less time than is required

by a typical student.

During his studies in the East he made the acquaintance of many prominent people

who would later help him further his career. With their help his first position

was as Government Physician for the Sioux at the Pine Ridge reservation in South

Dakota. He was at Pine Ridge before, during and after the “Ghost dance” rebellion

of 1890-91, and he cared for the wounded Indians after the massacre at Wounded Knee.

In 1891 he married a white woman who was also working at the Pine Ridge reservation,

Miss Elaine Goodale of Berkshire County, Mass. Shortly after returning from his

wedding in the East, the corrupt Indian agent forced Eastman to resign his job at

the agency in retaliation for Eastman’s attempt to help the Sioux prove crimes against

the agent and the agent’s white friends. In 1893 he, his wife and their new baby

moved to St. Paul, Minnesota, where he started a medical practice. Shortly thereafter

he accepted a position as field secretary for the International Committee of the

YMCA, and for three years traveled extensively throughout the United States and

Canada visiting many Indian tribes in an attempt to start new YMCA’s in those areas.

In 1897 Dr. Eastman went to Washington as the legal representative and lobbyist

for the Sioux tribe. From 1899 to 1902 he again served as a Government physician

to the Sioux at Crow Creek Agency, South Dakota. Starting in 1903, as an employee

of the Indian Bureau, he spent over six years giving permanent English family names

to the Sioux. In the process of creating both English names and family lineage records

he met and interviewed almost every living member of the Sioux tribe.

His first book, Indian Boyhood, was published in 1902. It is the story of

his own early life in the wilds of Canada, and it was an immediate public success

generating public notoriety and a demand for more of his writings. He wrote a total

of eleven books, including Red Hunters and the Animal People (1904), Old Indian

Days (1906), Wigwam Evenings (1909), Smoky Day’s Wigwam Evenings: Indian

Stories Retold (1910), The Soul of the Indian (1911), Indian Child Life (1913), Indian Scout Talks (1914), The Indian Today: The Past and Future

of the First American (1915), From the Deep Woods to Civilization (1916) Indian Heroes and Great Chieftains (1918). All of his books were

successful, some were used in school editions, and many were translated into French,

German, Danish, and Czech languages. He also contributed numerous articles to magazines,

reviews, and encyclopedias.

In 1910 Eastman began his long association with the Boy Scouts, helping Ernest Thompson

Seton establish the organization based in large part on the prototype of the American

Indian. It was also at about this time that he started to become in high demand

as a lecturer and public speaker, traveling extensively in the US and abroad. Eastman

was chosen to represent the American Indian at the Universal Races Congress in London

in 1911. His public speaking continued for the remainder of his life.

Beginning in 1910 and for the rest of his life, Eastman also became involved with

many progressive organizations attempting to improve the circumstances of the various

Indian tribes. At one time he was president of the Society of American Indians,

one prominent organization of that type.

From 1915 to 1920 the Eastman family created and operated a summer camp for girls,

Oahe, at Granite Lake, New Hampshire, attempting to teach Indian life-ways to young

girls.

He and his wife separated in August 1921. While the couple declined to comment on

the reason for their separation, descendants later commented that they believed

that the primary reason was the increasing dispute between the couple regarding

the best future for the American Indian. Elaine Goodale Eastman stressed total assimilation

of Native Americans into the dominant society and she apparently increasingly tried

to dominate her husband’s views.[1] Eastman favored a type of cultural

pluralism in which Indians would interact with the dominant society, utilizing only

those positive aspects that would benefit them, but still retaining their Indian

identity, including their traditional beliefs and customs; in effect living between

two worlds. Eastman believed that the teachings and spirit of his adopted religion

of Christianity and the traditional Indian spiritual beliefs were essentially the

same and had their common origins in the same “Great Mystery;” a belief that was

controversial to many Christians.

In 1928 Eastman purchased land on the north shore of Lake Huron, near Desbarats,

Ontario, Canada. For the remainder of his life, when he was not traveling and lecturing,

he lived there in his primitive cabin in communion with the virgin nature that he

loved so dearly. In his last years he spent only the coldest winter months with

his son in Detroit, where he died on January 8, 1939, at the age of eighty. For

several years toward the end of his life he worked on a major study on the Sioux,

but the project was never completed.

In his later adult life he was the foremost Indian spokesman of his day and his

contribution to our understanding of the American Indian philosophy and religion

are so significant that at the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair, Eastman was presented

a special medal honoring the most distinguished achievements by an American Indian.

The above biography of Charles Eastman (Ohiyesa)was excerpted from the biographical

notes at the end of The Essential Charles Eastman (Ohiyesa) (World Wisdom,

2007)

NOTES

[1] The

interviews on which these conclusions are based are set forth in detail in the most

authoritative biography on his life: Wilson, Raymond, Ohiyesa: Charles Eastman, Santee

Sioux , University of Illinois Press, Urbana, 1983.

|